Eloquent Silence: Nyogen Senzaki's Gateless Gate and Other Previously Unpublished Teachings and Letters. By Nyogen Senzaki, Roko Sherry Chayat, et al. Nov 1, 2008. 4.6 out of 5 stars 4. Paperback $5.90 $ 5. 90 $17.95 $17.95. Only 3 left in stock - order soon. Nyogen Senzaki, a Buddhist scholar of an international character to whom Reps acknowledged a deep debt of gratitude, was born in Japan. Early in life, he became a 'homeless monk,' wandering the land and studying from Buddhist monastery to monastery.

ZEN MESTEREK ZEN MASTERS

« Zen főoldal

« vissza a Terebess Online nyitólapjára

千崎如幻 Senzaki Nyogen (1876–1958)

Dharma name: 朝露如幻 Chōro Nyogen

Contents | |

PDF: Vasfurulya PDF:101 zen történet PDF: Százegy zen történet Tíz bika A tíz bika történet | PDF: The Iron Flute PDF: Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

DOC: 101 Zen Stories '10 Bulls' DOC:The Gateless Gateby Mumon (1228) PDF:Buddhism and Zen PDF:Reflections on Zen Buddhism PDF: Sufism and Zen Selected Poems of Jakushitsu |

Choro Nyogen, Dai Osho Choro Nyogen (1876-1958) is most usually referenced under the name Nyogen Senzaki Sensei. Choro means “morning dew” and Nyogen means “like a phantasm”. He himself commented many times on his pilgrimage as a nameless and homeless monk, remembering that he began life as an abandoned baby in Siberia, the son of a Japanese mother and a Russian father. A brilliant young student, he finished the Chinese Tripitaka by age 18, and became a monk. He loved his teacher, but came to reject what he called “Cathedral Zen” with its rather worldly hierarchy of titles and authority. He loved his years in Japan as priest of a little temple where he was a “hands-on” director of its kindergarten. When he set up a Zen center in San Francisco, he called it a “mentorgarden”. Strout McCandless reports that he once said “I want to be an American Hotei, a happy Jap in the streets”. (Ironically, he was interred in a camp during WWII). Senzaki actively searched for and encouraged Japanese Zen masters willing to come to the United States, and as Aitken Roshi comments “the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii, the Zen Center of Los Angeles, the Zen Studies Society in New York, and the Rochester Zen Center – all can trace their lineage through the gentle train of karma that Senzaki began.

DOC: The Gateless Gateby Mumon (1228)

Transcribed by Nyogen Senzaki & Paul Reps

First published in 1934 by John Murray, Los Angeles

This classic Zen Buddhist collection of 49 koans with commentary by Mumon was originally published in 1934, and later included in Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki's popular anthology Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. Due to non-renewal it is currently in the public domain in the US (although other parts of Zen Flesh, Zen Bones are not).

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Gateless_Gate

https://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/glg/index.htm

Table of Contents

Title Page

1. Joshu's Dog

2. Hyakujo's Fox

3. Gutei's Finger

4. A Beardless Foreigner

5. Kyogen Mounts the Tree

6. Buddha Twirls a Flower

7. Joshu Washes the Bowl

8. Keichu's Wheel

9. A Buddha before History

10. Seizei Alone and Poor

11. Joshu Examines a Monk in Meditation

12. Zuigan Calls His Own Master

13. Tokusan Holds His Bowl

14. Nansen Cuts the Cat in Two

15. Tozan's Three Blows

16. Bells and Robes

17. The Three Calls of the Emperor's Teacher

18. Tozan's Three Pounds

19. Everyday Life Is the Path

20. The Enlightened Man

21. Dried Dung

22. Kashapa's Preaching Sign

23. Do Not Think Good, Do Not Think Not-Good

24. Without Words, Without Silence

25. Preaching from the Third Seat

26. Two Monks Roll Up the Screen

27. It Is Not Mind, It Is Not Buddha, It Is Not Things

28. Blow Out the Candle

29. Not the Wind, Not the Flag

30. This Mind Is Buddha

31. Joshu Investigates

32. A Philosopher Asks Buddha

33. This Mind Is Not Buddha

34. Learning Is Not the Path

35. Two Souls

36. Meeting a Zen Master on the Road

37. A Buffalo Passes Through the Enclosure

38. An Oak Tree in the Garden

39. Ummon's Sidetrack

40. Tipping Over a Water Vase

41. Bodhidharma Pacifies the Mind

42. The Girl Comes Out from Meditation

43. Shuzan's Short Staff

44. Basho's Staff

45. Who Is He?

46. Proceed from the Top of the Pole

47. Three Gates of Tosotsu

48. One Road of Kembo

49. Amban's Addition

Nyogen Senzaki, Eloquent Silence

Nyogen Senzaki's Gateless Gate and Other Previously Unpublished Teachings and Letters

edited and introduced by Roko Sherry Chayat; foreword by Eido Shimano

Wisdom Publications, 2008, 456 pages

The most comprehensive collection available of Nyogen Senzaki's brilliant teachings, Eloquent Silence brings new depth and breadth to our knowledge and appreciation of this historic figure. It makes available for the first time his complete commentaries on the Gateless Gate, one of the most important and beloved of all Zen texts, as well as on koans from the Blue Rock Annals and the Book of Equanimity. Amazingly, some of these commentaries were written while Senzaki was detained at an internment camp during WWII. Also included are rare photographs, poems reproduced in Senzaki's beautiful calligraphy and accompanied by his own translations, and transcriptions of his talks on Zen, esoteric Buddhism, the Lotus Sutra, what it means to be a Buddhist monk, and other subjects. Roko Sherry Chayat has edited Nyogen Senzaki's words with sensitivity and grace, retaining his wry, probing style yet bringing clarity and accessibility to these remarkably contemporary teachings.

Table of Contents

Foreword by Eido Shimano xiii

Introduction by Roko Sherry Chayat 1

Acknowledgments 23

Photographs 27

Part I: Commentaries on the Gateless Gate 35

Introductory Comments 37

Mumon's Introduction 40

Case One: Joshu's Dog 43

Case Two: Hyakujo's Fox 47

Case Three: Gutei's Finger 51

Case Four: A Beardless Foreigner 54

Case Five: Kyogen's Man in a Tree 57

Case Six: Buddha Twirls a Flower 60

Case Seven: Joshu's 'Wash Your Bowl' 63

Case Eight: Keichu's Wheel 67

Case Nine: A Buddha before History 70

Case Ten: Seizei Alone and Poor 74

Case Eleven: Joshu Examines a Hermit Monk in Meditation 77

Case Twelve: Zuigan Calls His Own Master 80

Case Thirteen: Tokusan Holds His Bowls 83

Case Fourteen: Nansen Cuts the Cat in Two 87

Case Fifteen: Tozan's Three Blows 91

Case Sixteen: The Bell and the Ceremonial Robe 94

Case Seventeen: The Three Calls of the Emperor?s Teacher 97

Case Eighteen: Tozan's Three Pounds 100

Case Nineteen: Everyday Life Is the Path 104

Case Twenty: The Man of Great Strength 107

Case Twenty-one: Dried Dung 110

Case Twenty-two: Kashyapa's Preaching Sign 113

Case Twenty-three: Think Neither Good, Nor Not-Good 116

Case Twenty-four: Without Speech, Without Silence 121

Case Twenty-five: Preaching from the Third Seat 124

Case Twenty-six: Two Monks Roll Up the Screen 127

Case Twenty-seven: It Is Not Mind, It Is Not Buddha, It Is Not Things 130

Case Twenty-eight: Ryutan Blows Out the Candle 133

Case Twenty-nine: Not the Wind, Not the Flag 137

Case Thirty: This Mind Is Buddha 141

Case Thirty-one: Joshu Investigates 144

Case Thirty-two: A Philosopher Asks Buddha 147

Case Thirty-three: This Mind Is Not Buddha 151

Case Thirty-four: Wisdom Is Not the Path 154

Case Thirty-five: Two Souls 158

Case Thirty-six: Meeting a Master on the Road 163

Case Thirty-seven: The Cypress Tree in the Garden 166

Case Thirty-eight: A Buffalo Passes through an Enclosure 169

Case Thirty-nine: Ummon's Off the Track 172

Case Forty: Tipping Over a Water Vessel 175

Case Forty-one: Bodhidharma Pacifies the Mind 178

Case Forty-two: The Woman Comes Out from Meditation 182

Case Forty-three: Shuzan's Short Staff 185

Case Forty-four: Basho's Staff 188

Case Forty-five: Who Is It? 191

Case Forty-six: Proceed from the Top of the Pole 194

Case Forty-seven: The Three Barriers of Tosotsu 197

Case Forty-eight: One Path of Kempo 200

Amban's Addition 203

Part II: Commentaries on the Blue Rock Collection 207

Case One: I Know Not 209

Case Two: The Ultimate Path 211

Case Eight: Suigan's Eyebrows 213

Case Twelve: Tozan's Three Pounds of Flax 216

Case Twenty-two: Seppo's Cobra 218

Part III: Commentaries on the Book of Equanimity 221

Introduction 223

Chapter One: Buddha Takes His Preaching Seat 226

Chapter Two: Bodhidharma Walks Out from Samskrita 229

Part IV: Dharma Talks and Essays 235

An Ideal Buddhist 237

A Meeting with Sufi Master Hazrat Inayat Khan 242

Seven Treasures, Part One 244

Seven Treasures, Part Two 250

Seven Treasures, Part Three 254

The Ten Stages of Consciousness 258

Emancipation 261

How to Study Buddhism 266

Zen Buddhism in the Light of Modern Thought 269

Buddhism and Women 273

Obaku?s Transmission of Mind, Part One 277

Obaku?s Transmission of Mind, Part Two 280

Obaku?s Transmission of Mind, Part Three 282

Obaku?s Transmission of Mind, Part Four 286

Esoteric Buddhism in Japan 289

Shingon Teachings 296

What Is Zen? An Evening Chat 299

What Does a Buddhist Monk Want? 305

On Zen Meditation 309

On The Lotus of the Wonderful Law:

Introducing Soen Nakagawa 315

Bankei?s Zen 322

Part V: Calligraphies and Selected Poems 325

'Basho' 327

'Opening words of Wyoming Zendo' 328

'Evacuees make poinsettia' 329

'Autumn came naturally' 330

'In this part of plateau' 331

'This desert on the plateau' 332

'My uta (Japanese ode)' 333

'Those who live without unreasonable desires' 334

'The mother was named an enemy-alien' 335

'Naked mountains afar!' 336

'No spring in this plateau' 337

'Closing the meditation hall' 338

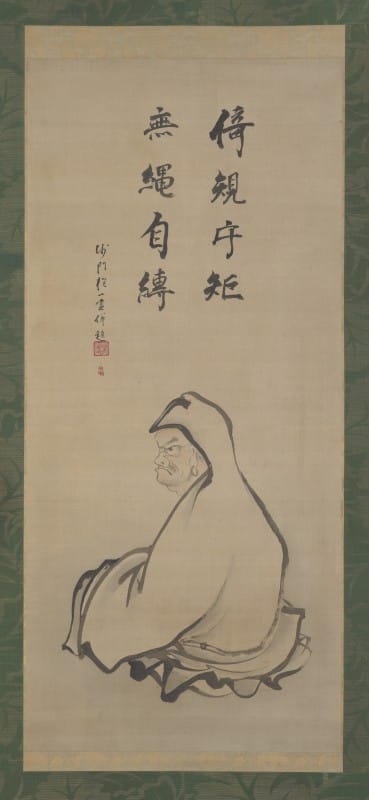

'Bodhidharma' 339

'This world is the palace of enlightenment' 340

'Until now the radiant moon' 341

Bodhidharma Commemoration 343

Celebration of Buddha?s Birth 343

Translations of Three Poems by Jakushitsu: 344

Ryo-Ryo (Loneliness) Ko-Fu (Old Way) 344

Free Hands 344

The House of Evergreen: Sosui-An 345

Commemoration of Soyen Shaku 345

Thirty-third Commemoration of Soyen Shaku 346

Part VI: The Autobiography of Soyen Shaku

(Translated and with Comments by Nyogen Senzaki) 347

Part VII: Correspondence 363

To Soyen Shaku, December 25, 189? 365

To Soyen Shaku, March 21, 1905 378

The Purpose of Establishing Tozen Zenkutsu, April 8, 1931 382

Article and Related Letters to the Editor, Second General Conference of Pan-Pacific Young Buddhist Associations, 1934 384

Exchange with Myra A. Stall, July 11 and 16, 1956 402

Notes 407

Bibliography 411

Index 313

PDF: Reflections on Zen Buddhism

by Nyogen Senzaki

The following articles originally appeared in Pacific World I, no. 2 (September 1925): pp. 40–42, 56; Pacific World II, no. 2 (March 1926): pp. 41, 48; and Pacific World II, no. 6 (May 1926): pp. 57, 71.

The Last Statement of Nyogen Senzaki

Eloquent Silence Nyogen Senzaki

In Memoriam Nyogen Senzaki (1876-1958)

In: The Iron Flute : 100 Zen Kōan with commentary by Genrō, Fūgai and Nyogen.

Translated and edited by Nyogen Senzaki and Ruth Strout McCandless;

C. E. Tuttle, Ruthland, Vt. & Tokyo, 1961, pp. 159-165.

Sōen Shaku on Nyogen Senzaki

IF THE hitting of Tê-shan’s big stick covers me like rain, I will not

be frightened. If the shouting of Lin-chi’s “Katsu!” roars like a

thunderstorm, I will not be surprised. If Punna’s sermons are as

fluent as running water and Shariputra’s wisdom sparkles like the

morning star, I will not envy them. If one keeps the precepts,

consecrates his life, lives alone in a mountain hut, takes his meal

once a day, fasts often, makes his body transparent with pure food,

and performs Buddhist ceremonies six times a day, but lacks the

vow to save all sentient beings, I cannot encourage myself to

respect him.

My idea is shown in the Saddharma-pundarika Sutra as a

character named “ Bodhisattva Never-Despised.” If in our day a

Bodhisattva accomplishes realization of selflessness, using his

hands only for loving-kindness as a mother cares for her baby,

walks the road of life to serve him, rocks the cradle to comfort him,

and thinks of all boys and girls as her own children, so a monk

considers all workers on the different stages as his companions,

makes a home without wife or children, gathers mentors with no

discrimination of guest and host, speaks plain humanity, implying

Buddha-nature, he will certainly bring my admiration and make

me shed tears of sympathy. I wonder, how many monks or priests

such as this are among the hundred thousand Buddhist workers in

Japan?

Monk Nyogen tries to live the Bhikkhu’s life according to the

teaching of Buddha, to be non-sectarian with no connection to a

temple or headquarters; therefore, he keeps no property of his own,

refuses to hold a position in the priest-hood, and conceals himself

from noisy fame and glory. He has, however, the four vows—

greater than worldly ambition, with Dharma treasures higher than

any position, and loving-kindness more valuable than temple

treasures. He walked out of my monastery and now wanders around

the world, meeting young people, associating with their families,

and making religion, education, ethics, and culture the steps to

climb to the highest. He is still far from being a “ Bodhisattva

Never-Despised,” but I consider him as a soldier of the crusade to

restore the peaceful Buddha-land for all mankind and all sentient

beings. Every step of continuation means success to him for this

sort of endless work. I congratulate him this very moment.

Autumn 1901

Engaku Monastery

Kamakura

Nyogen Senzaki Books

An Autobiographical Sketch

As Told to One of His Students

YOU HAVE asked me about my past training and my work in

America. I am merely a nameless and homeless monk. Even to

think of my past embarassess me. However, I have nothing to

hide. But, you know, a monk renounces the world and wishes to

attract as little attention as possible, so whatever you read here you

must keep to yourself and forget about it.

My foster father began to teach me Chinese classics when I

was five years old. He was a Kegon scholar, so he naturally gave

me training in Buddhism. When I was eighteen years old, I had

finished reading the Chinese Tripitaka, but now in this old age I

do not remember what I read. Only his influence remains: to live

up to the Buddhist ideals outside of name and fame and to avoid as

far as possible the world of loss and gain. I studied Zen in the Sōtō

school first, and in the Rinzai school later. I had a number of

teachers from both schools, but I gained nothing. I love and respect

Sōen Shaku more than all other teachers, but I do not feel like

carrying all my teachers’ names on my back like a sandwich man;

it would almost defile them.

In those days one who passed all kōans called himself the first

and best successor of his teacher and belittled others. My taste does

not agree with this manner. It may be my foster father’s influence,

but I have never made any demarcation of my learning, so do not

consider myself finished at any point. Even now I am not

interested in inviting many friends to our meetings. You may

laugh, but I am really a mushroom without a very deep root, no

branches, no flowers, and probably no seeds.

After my arrival in this country in 1905 , I simply worked through

many stages of American life as a modern Sudhana—meditating

alone in Golden Gate Park or studying hard in the public library of

San Francisco. Whenever I could save money, I would hire a hall

and give a talk on Buddhism, but this was not until 1922. I

named our various meeting places a floating Zen-dō. At last in

1928 I established a Zen-dō, which I have carried with me as a

snail his shell; thus, I came to Los Angeles in 1931. I feel only

gratitude to my teachers and all my friends, and fold my hands

palm to palm.

Nyogen Senzaki on His Zen-dō

BODHISATTVAS:

In the beginning this place was selected by some Japanese

Buddhist friends as a shelter for Buddhist monks. My ideal as a

Buddhist monk is to have no permanent place to stay, but to take

a course of pilgrimage as a lone cloud floating freely in the blue

sky. Even though I have been staying in this place two years and

five months, I have always considered myself a pilgrim on a

journey, making each a day a transient stay. As it is a transient

stay, I do not worry about tomorrow. It is today I am living with

gratitude. What can my regret do with the happenings of

yesterday? If I have to go away for a long trip, some other monk or

monks may stay in this shelter, transiently, the same as I. As long

as this principle of Anikka, the principle of impermanence, is

practiced, this shelter will remain a Buddhist house. In fact, I am

passing away every day. What you saw about me yesterday, you

cannot see any more. Tomorrow you will meet a man who looks

like Senzaki, but he is not the Senzaki you met today. As long as

you dwell in the understanding of Anatta, the principle of nonindividuality,

our relation will be Buddhistic.

If any of you have a desire to move our meditation hall to

another location to increase your comfort and pleasure, you are

clinging to delusions which are not Buddhistic at all. True

Buddhists never proselytize. I did not ask you to come to this

place; your own Buddha-nature guided you here. If a new location

and a better house would attract more people, what would be the

use of them if we had no Buddhist spirit within ourselves? Some

may say they are satisfied with this location and house, but for the

sake of strangers we must make it more attractive. This world is

nothing but the phenomena of dissatisfaction. Wherever one goes,

one must face some sort of suffering. This is the principle of

Dukkha, the principle of suffering, which Buddha repeatedly

stressed. Those who come for comfort and pleasure will never be

satisfied in a Buddhist house. They have not belonged here from

the beginning, so why should we try to attract them? This house

is a shelter for Buddhist monks, and you, our honorable guests,

should feel obliged to follow its principles. If you wish to

meditate, I will join you in meditation. If you wish to study

scriptures, I will assist your learning. If you wish to take the vows

to keep the precepts, I will ordain you as monks, nuns, upasakas,

or upasikas, and will endeavor to live the Buddhist life with you.

If you wish to donate material or immaterial things, the monks

will receive them in the name of the Dana-paramita. You need not

worry how and where your seeds of charity are planted. Just give

and forget. This is the way to maintain the Sangha, the group of

practical Buddhists. No guest of the Buddhist house should worry

about spreading the teaching or maintaining the movement. His

time should be utilized in meditation, understanding the

scriptures, and practicing what he is learning in his own world.

This is the true spirit by which the teaching of Buddha will remain

among mankind in its proper form.

Of course, I have no objection to your starting your own

movement with the understanding you have attained, but while

you are coming to this meditation hall, I wish you to be the

“ silent partner” of Zen. Throw out your ideas of teaching others,

and devote yourselves to study—there are one thousand seven

hundred kōans that you have to pass. There are five thousand

books on Buddhism in European languages, which require your

reading. And as for realization, once you think you have attained

something, you will find yourself ten thousand feet below and have

to start at the bottom again.

I am telling you this in such a severe way because I want you

to attain the real, Buddhist enlightenment. There are many

teachings from the Orient, but none of them can lead you to true

enlightenment, true emancipation, except Zen Buddhism. They

may satisfy your worldly desires, which they call spiritual

attainment, but they will not lead you to the highest stage of

Nirvana; you will drop to the world of dust again as an arrow shot

toward the heavens falls to earth. What I say is the echo of my

teacher’s wisdom, and what my teacher told me is the wisdom of

his teacher. We can trace directly through history seventy-nine

generations of teachers to Buddha Shakyamuni. I shall tell you

how to discipline yourselves until you are ready to practice Zen

meditation. I could give you a longer discourse, but until you are

ready to enter Samadhi, the more you hear about the theories and

speculations, the more you will carry the unnecessary burden upon

your shoulders.

I wish all of you to come practice the true Buddhism,

following the discipline of Zen monks, and forgetting your own

self-limited, worldly opinions.

September 19, 1933