The practice of 'just sitting,' also known as mindfulness meditation or by its Japanese name, zazen (or zuochan in Chinese), is the central practice method utilized in Pragmatic Buddhism. Each week, CPB monks, formal students, members and guests join as a community to practice zazen. This communal setting enhances our individual practice just like any shared experience, as the group calls on the individuals to remain focused on the practice at hand. Unlike many forms of meditation where the goal is to block out the external world to focus internally, zazen pays attention to all sensory experiences, and is therefore called 'awareness cultivation' at the Center for Pragmatic Buddhism. This practice is essential to 'train the brain' to pay more attention throughout our everyday lives, so that we might embrace a deep awareness without attaching unnecessary linguistic labels to our experiences. This may be called nonjudgmental awareness.

Once the body’s posture is balanced and settled, attention should be turned to the breathing. In many ways the breathing, which links and integrates body and mind, is the most important aspect of zazen. In zazen, one becomes fully aware of and open to each in-breath and out-breath. The practice of 'just sitting,' also known as mindfulness meditation or by its Japanese name, zazen (or zuochan in Chinese), is the central practice method utilized in Pragmatic Buddhism. Each week, CPB monks, formal students, members and guests join as a community to practice zazen.

A major goal of awareness cultivation is to become aware of our own mental dispositions. No matter what you observe (anger, stoicism, happiness, sadness, etc), it is important for you to know intimately your own mind, so that you can identify the negative characteristics (greed, hatred, resentment, self-loathing, dogmatic views, etc). By becoming aware of negative aspects of our intentionality, we can work—through regular zazen training and the nonjudgmental awareness that results—to let them go. At the same time we are working on 'letting go,' we actively engage perspectives and attitudes that are positive and healthy for us. In Pragmatic Buddhism, positive and healthy perspectives and attitudes include an awareness of interconnectivity, interdependence and the genuine extension of altruism and pluralism that results.

While practicing zazen, the human brain actually changes its physiology to induce a more relaxed and deeply calm state of awareness. Over time the brain itself changes its underlying structure to increase the capacity for awareness. Thus, with experience, the brain is able to remain aware of more aspects of our daily life than before training began. If we have an increased capacity for awareness, we are better able to navigate our world with effectiveness and happiness. Because of this insight from modern science, we see that there is more to zazen than 'just sitting'! See our 'Meditation & Health' section for more information about the changes that take place after regular zazen practice.

Location, Timing and Meditation Supplies

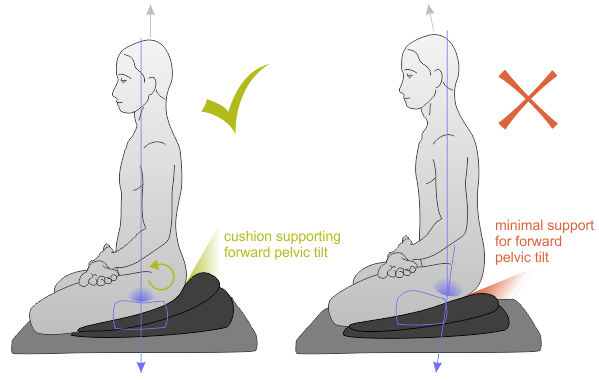

Remaining mindful of the location for your practice, as well as the timing are essential in regular zazen practice. A quiet and comfortable environment, such as a bedroom in your home that can be closed off from other human voices will work well. During comfortable times of the year, the outdoors is an excellent setting. It is preferable that you sit around the same time each day—when possible—as our bodies get accustomed to cyclical schedules, and this facilitates the meditative mindset. We truly are creatures of habit, and this can be a healthy and positive characteristic for regular practice, particularly once that practice is firmly established. Proper sitting supplies, such as a zafu (meditation cushion) and zabuton (under-cushion), or a seiza bench are very helpful; simpler everyday items, such as a large pillow from your home can work wonders when formal practice supplies are not available.

Zafu

Zabuton

Seiza Bench

The Posture

The most important part of sitting for meditation is proper centering and balance; if these two elements are not observed first, the body will fatigue more quickly and pain or discomfort in the postural muscles of the back might distract the practitioner from his or her sitting practice. Additionally, relaxation of muscular tension is a requisite to a good zazen posture.

A Note About Joint Health: Before attempting to sit in any of the traditional meditative postures outlined here (all except the 'chair' position), be sure that your bodily joints, especially the hips, knees and ankles are healthy enough for the posture. If you have had or have arthritis, degeneration or surgeries, be sure to check with your physician prior to engaging the postures listed here. For many, mild stretching exercises prior to sitting will be sufficient to 'warm' the muscles and greatly enhance comfort. If you are unsure, however, progress slowly and begin with more conservative postures, such as sitting in a chair.

Begin by situating yourself over your meditation cushion (zafu), and then assume one of the four recommended meditation postures. The Center for Pragmatic Buddhism teaches four primary meditation postures: 1) half lotus, 2) Burmese, 3) seiza, and 4) chair (see examples below). In the preferred posture, bring yourself upward and forward, so that most of your weight is transferred into the legs. Now slowly and mindfully relax back into an upright posture, and then exhale, allowing all muscular tension to fall away from the neck and shoulders downward. Next allow the belly to relax outward so that you can utilize deep breathing (from the diaphragm), and then be sure the head is centered over the neck instead of leaning forward and downward.

Half Lotus

The half lotus is like the lotus except that only the non-dominant foot is tucked into the dominant thigh. Thus, if you are right-handed, your right foot and leg will be flush against the ground and the left foot will be tucked into the right thigh at the knee; the left knee will go as close as possible to the ground for proper balancing.

Burmese Posture

The Burmese style posture is like the half lotus, except the non-dominant foot is not tucked, and instead is placed along the ground in front of the dominant leg, allowing for a more centered posture in those who are less flexible than the half lotus requires.

Seiza Posture

With the seiza posture, place the legs parallel to one another and flush to the ground, with toes pointed behind you. It is especially important to have a soft mat or zabuton to prevent discomfort while sitting in seiza.

Chair

For those who are unable to sit in a traditional posture, sitting in a chair, while retaining the principles of proper centering and balance, will work just fine!

Recently, a fellow practitioner at Berkeley Zen Center sent me an email with this direct question: “I’m wondering what you do when you do zazen?” Much as I have thought about it, and irrespective of the countless times I’ve given zazen instruction, I’ve never written out my way of zazen, step-by-step. So I will try to do that here, leaving out some of the detail and fine points of posture, although these details are all-important. The fine points have been beautifully articulated by Dogen Zenji in Fukanzazengi, in Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, and by so many of our teachers. What I share of “my way” stands on the shoulders (or sits in the shadows) of giants.

***

From the moment I sit down in zazen—whether I sit cross-legged in half-lotus position or in a chair—from that moment everything is zazen. No preliminaries, no getting ready to sit. Zazen includes each activity. The first thing I do is to establish a stable upright posture, particularly making an effort to build my posture up from the small of my back, the base of the spine, lifting my sternum so that my upper body is open and relaxed. I like the expression “strong back, soft front.” Integral to zazen posture is the “cosmic mudra”—left hand on top of the right palm, thumb tips just barely touching. The mudra rests against my body or in my lap. It forms a half-circle that is capable of holding the universe.

Zazen Posture Youtube

With this upright posture set, I take four or five breaths through my mouth, inhaling deeply, exhaling slowly and steadily, making the exhalation last as long as it can, pushing out the remaining air at the end of the breath. A deep inhalation, which naturally follows, refreshes me. After four or five breaths like this, I settle into a more “ordinary” breath, breathing through my nose, allowing the breath to reach down to my hara or belly in a relaxed manner.

Establishing posture and natural breathing, I take a few moments to set my intention, invoking bodhicitta, the mind of enlightenment for and with all beings. This is is embodying Dogen Zenji’s admonition in Gakudo Jojin-shu: “You should arouse the thought of enlightenment.” I have created a simple phrase for myself that I place silently on my breath, repeating it three times: “May I be awake that others may awaken.” It feels as if I am lightly dropping these words into the quieting pool of zazen, letting the ripples spread as they will.

Honestly, I cannot say what happens for the remainder of the zazen period. I make no effort to remember, and I don’t remember. That’s fine, because there is nothing I am trying to accomplish. The effort is to be awake and receptive to the flow of sensations, perceptions, and thoughts that arise and fall away as they will. But this is not drifting and dreaming. Rather, a kind of fluid alertness, capable of including each thing without being caught on it.

This alertness calls for an element of concentration, samadhi, which, of course, is a step on the Eightfold Path. Concentration arises from our posture, which is never slack. From time-to-time I give myself zazen instruction, checking my mudra and each point of posture, making an effort to re-align my body. Concentration also arises with breathing. Often, I do breath-counting, susokan in Japanese, lightly counting ten breaths, one at a time, giving each breath a silent count on the exhalation and contraction of my belly. I find that a whole world can arise in the space of a single breath—a world of sense receptivity, or a world of distracted thinking. If I lose count, I start over again at one, leaving behind all judgments and distractions.

Sometimes I do an alternative breath practice—”Just This.” Breathing in on the word “Just,” breathing out on “This.” In time, counting or words fall away and there is just the rhythmic rise and fall or breath, the unencumbered flow of mind. The bell rings, drawing me up from the depths and back into the world of so-called ordinary thoughts.

This approach to susokan, sliding into shikantaza—just sitting—is what I understand Dogen Zenji to means as “think not-thinking.” Mind fades but does not disappear. This is not sleep or trance, but a mind that is fresh as an autumn breeze. My senses are functioning, but not actively. That is, I am seeing, but not looking. Hearing, but not listening. Thoughts may arise, but I am not stringing them into stories.

How To Do Zazen Meditation

Zazen Positions

My experience over the years is that the mind of zazen reaches far beyond the zendo and permeates my everyday activity. Sometimes no more than a single mindful breath is sufficient to enter the dharma gate of zazen. But, don’t take my word for it. Try it yourself.